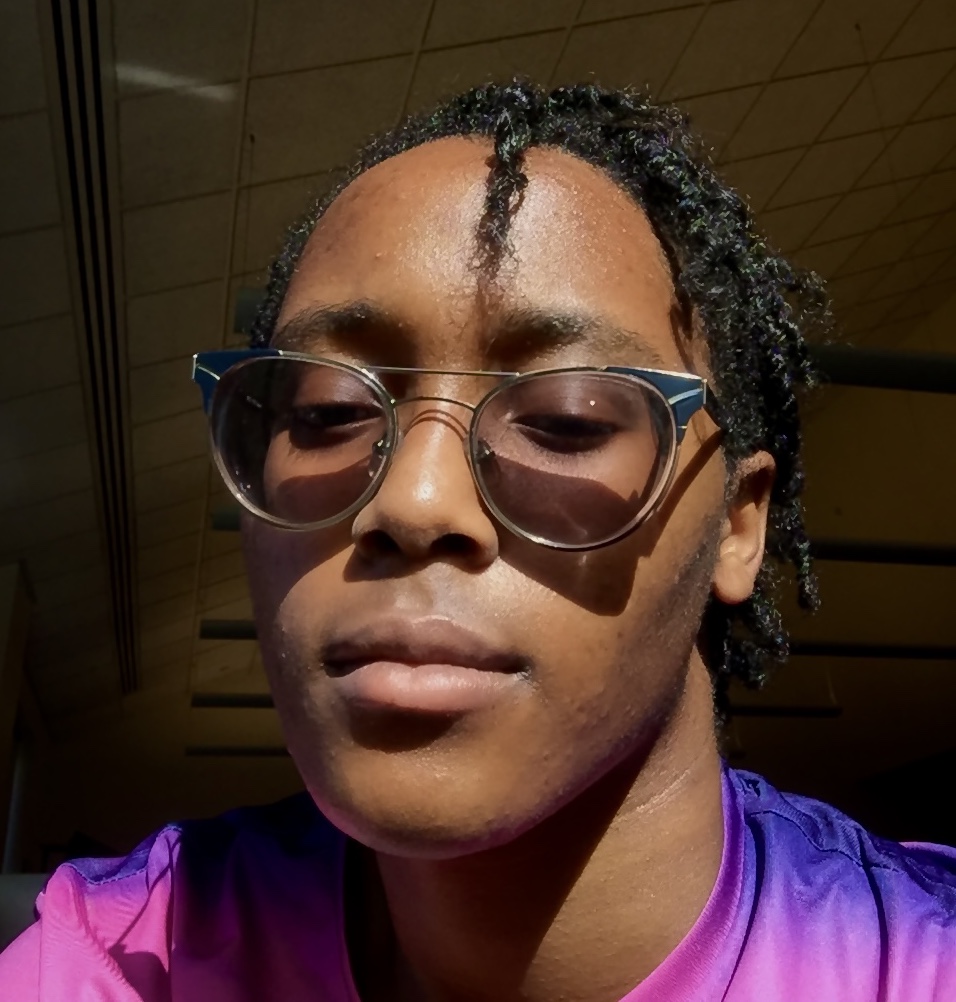

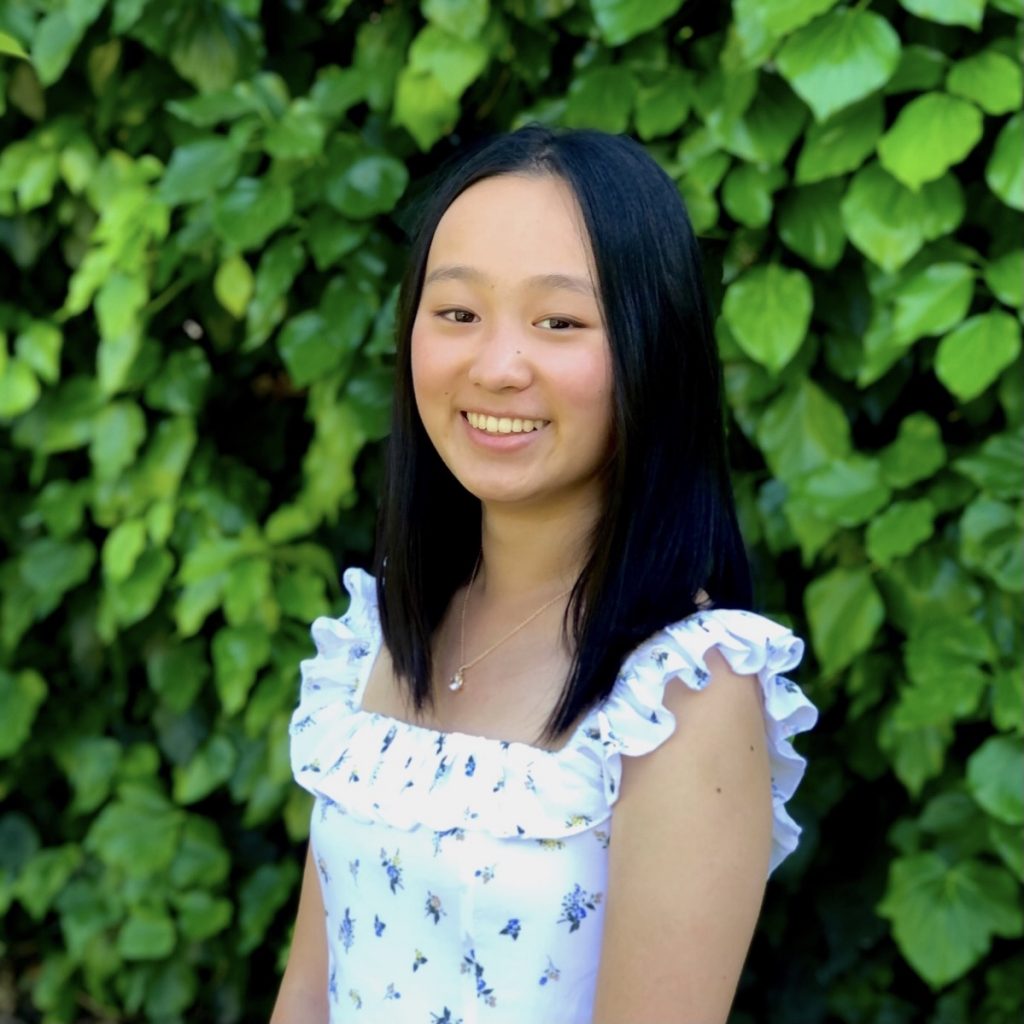

Ahead of our conversation event with Krystal Tsosie and Tao Leigh Goffe, which James Fenelon will moderate, the Aydelotte student fellows researched places where the work of IndigiData and Dark Laboratory intersect. The result is an overview that touches on linked concerns of data sovereignty, the entanglement of Black and Indigenous struggles and ways of knowing, and the history of higher education’s engagement with and incorporation of these concerns.

What is data sovereignty?

Perhaps the most familiar use of the term “sovereignty” comes from the categorization of Native American tribes as sovereign nations. So how can data be sovereign or have sovereignty? And how do Indigenous self-governing peoples, whose state of sovereignty is questioned by state policy and practice, govern data collected about them or by them?

In one sense, data sovereignty is a legal term. Much like any other form of property, data collection and ownership are subject to regulation by the government. In the context of the contemporary digital age, data has become synonymous with online records, and the legal term, “data sovereignty,” deals with issues of cybersecurity and online privacy.

However, the definition of data can expand beyond the realm of the technological to mean information of all formats and content. In the context of the Indigenous data sovereignty movement, “data” means anything from Indigenous oral traditions and art to genetic information, and its “sovereignty” is the ability for Indigenous communities to regulate data collected by and about them. The goal is to have Indigenous communities decide who belongs to their community and can have their data counted, have access to this data, and control over what gets collected.

What kind of data are considered within data sovereignty?

Government Collection

Perhaps the most frequently discussed issue in Indigenous data sovereignty is that of the United States Census. The Census Bureau’s methodology means that Indigenous communities often don’t get access to information that could be useful, either because the definition of who is a tribal member is different on the federal level or because the government will not provide communities access to data by citing privacy and confidentiality laws.

Indigenous Collection

Data collected by Indigenous communities includes Indigenous oral traditions, environmental surveys, cultural heritage materials, and demographic data. Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear cites as an example the Winter Counts of the Lakota, Blackfeet and other Plains tribes which recorded “numbers of tribal citizens, allies, enemies, wild game, [and] lodges” on animal hides. This kind of data collection has long been integral to the culture of Indigenous peoples.

Researcher Collection

Academic researchers—including Native and non-Native people—have a longstanding interest in collecting data from Indigenous communities. This can include biological samples like DNA, blood, microbial flora, or archeological information like art, oral histories, or stories from Indigenous communities.

Why is data sovereignty important?

There is a history of Indigenous communities being positioned in what Stephanie Russo Carroll, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear and Andrew Martinez describe as “a paradox of scarcity and abundance: extensive data are collected about Indigenous peoples and nations, but rarely by or for Indigenous peoples’ and nations’ purposes.” Data may be collected about Indigenous people by researchers, but they are not given full access or control over its use. Instead of information being given back to tribal governments in order to assist them in their own policy making, it has been often been used to build impoverished narratives that seek to make Indigenous communities into objects of federal policy. This narrative has tangible results on laws and funding, as well as lasting cultural and social implications.

One example of this is research on blood samples from the Havasupai Tribe in 1989, which were originally obtained for research on diabetes, but then were subsequently used “to study many other things, including mental illness and theories of the tribe’s geographical origins that contradict their traditional stories.”

Indigenous data sovereignty aims to prevent unethical research and data usage by claiming control for Indigenous people.

What are the tenets of data sovereignty?

Matthew Snipp suggests that there are three key tenets of data sovereignty that define Indigenous communities’ sovereignty over their data. To establish Indigenous data sovereignty, Indigenous nations and communities must have control over the privacy, confidentiality, and membership aspects of data collection.

1. Sovereignty over privacy: what data is collected

Some information like participation in religious ceremonies or hunting practices may be considered private information for a tribal community and collecting this information may be “intrusive at a minimum or even threatening and potentially harmful.”

2. Sovereignty over confidentiality: who the data gets shared with

Tribal communities should be able to have access to data collected about them. “There is a great deal of data collected by the Census Bureau and other agencies, such as the Indian Health Service, that are not accessible to smaller tribal communities.”

3. Sovereignty over membership: who counts under the criteria of the data

“Indigenous communities should be empowered to determine who belongs among them and who should be excluded for the purposes of data collection.”

Why might storytelling be considered data?

Indigenous stories have been recorded and used by anthropologists to understand Indigenous history and traditions; such stories can also be considered Indigenous data and subject to Indigenous data sovereignty standards. In fact, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples specifically grants sovereignty over this kind of data:

Article 31: Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

On the one hand, this highlights the reach and ramifications of data sovereignty across multiple forms of knowledge transmission. On the other hand, the need to expand the concept of “data” to include narratives signals the limitations of certain bounded means of Western disciplinary thinking. This resonates, too, with how Larry Neal described the Black Arts Movement, a foundational part in the rise of Black Studies: “We advocate a cultural revolution in art and ideas. The cultural values inherent in western history must either be radicalized or destroyed, and we will probably find that even radicalization is impossible. In fact, what is needed is a whole new system of ideas.”

A whole new system of ideas—in terms of both decolonization and Black cultural revolution—suggests that storytelling reconfigures our ideas of data and intimates the wider knowledge-making power that storytelling offers for Black and Indigenous peoples.

What has been written about solidarity between Black and Indigenous peoples? Are there recent examples of this activity?

Yes! Black-Indigenous solidarity has come to the forefront in recent years as #NoDAPL (Protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline) and the Black Lives Matter movement have both had support from both Black and Indigenous activists and groups grounded in Black and Indigenous solidarity. In an essay for the collection, Standing with Standing Rock, Kevin Bruyneel points out that the Black Lives Matter statement of solidarity with Standing Rock highlights both the complexities of this question and the myriad areas of mutual interest:

As there are many diverse manifestations of Blackness, and Black people are also displaced Indigenous peoples, we are clear that there is no Black liberation without Indigenous sovereignty. Environmental racism is not limited to pipelines on Indigenous land, because we know that the chemicals used for fracking and the materials used to build pipelines are also used in water containment and sanitation plants in Black communities like Flint, Michigan.

What is the wider import of storytelling and why might the practice require support?

The short answer is that stories offer a critical form for knowing the world. The philosopher Sylvia Wynter even suggests that humans are homo narrans, a species defined by the coordinated phenomenon of the brain’s evolution and the capacity for language and storytelling. Nevertheless, stories and storytelling often are marginalized when faced with methods that are figured as more objective.

Katherine McKittrick describes stories as an “aesthetic relationality that relies on the dynamics of creating-narrating-listening-hearing-reading-and-sometimes-unhearing.” And while McKittrick’s focus resides on stories of Black worlds and ways of being, her sense of stories as interdisciplinary methods built in relation for the practice of life against a racist world offers a broad description of the varied praxis and possibility of storytelling for Indigenous peoples.

Why are these questions related to higher education?

Higher education cannot be separated from the history of settler colonialism and race and racism within the United States. The scholar Craig Wilder has famously argued that “the academy never stood apart from American slavery—in fact, it stood beside church and state as the third pillar of a civilization built on bondage.” While Wilder’s book focuses primarily on American higher education’s relationship to slavery, he also attends to the fact that “colleges were among the colonial institutions that braided histories [of the people of the Atlantic world] and rendered their fates dependent and antagonistic.” Sandy Grande speaks to this directly in Red Pedagogy recounting that “by the mid-eighteenth century Harvard University, the College of William and Mary, and Dartmouth College had all been established with the charge of ‘civilizing’ and ‘Christianizing’ Indians as an inherent part of their institutional missions.”

These activities extend beyond the eighteenth century. The 1862 Morrill Act, signed by Abraham Lincoln, transferred ownership of 10.7 million acres of stolen Indigenous land to what would become 52 land grant universities. This transfer took the form of actual land occupation and land scrip, meaning the wealth from this action still holds within university endowments.

Higher ed is a key site for Indigenous and Black data collection, and it is therefore also a key site for the repair and restitution of past violations of data sovereignty, and for forward-looking changes that seek to make data sovereignty a norm. The prestige and power of research institutions have been tied to their access to research subjects who could be exploited. There remain disputes over the ownership, access, and financial gain accrued by the use of Henrietta Lacks’s famously immortal cells, known as HeLa cells. Intellectual property laws and scientific practices make it difficult to attribute direct financial gain to the Johns Hopkins Hospital, where Lacks was treated for cervical cancer in 1951. It has nevertheless remained something of an open secret that the hospital’s “charity” to Black patients supplied a steady stream of research subjects; as Lacks’ physician stated, Hopkins had “no dearth of clinical material” because of its proximity to a “large indigent Black population.” In the form of research potential, that abundance made possible the hospital’s prominence. Aspects of the Lacks case are similar to the case of the improper use of Havusupai Tribe blood samples in 1989 by a researcher at Arizona State University. The greater affordance of technology transfer rights to research universities made possible by the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 have only intensified a profit-motive embedded within biomedical research of this kind.

These concerns also extend into the university’s position as an entity for legitimating knowledge, in its research, teaching, and institutional practices. Historical and present struggles for the establishment of Black, Ethnic, and Indigenous Studies departments, the advantageous institutional “use of minority difference” as Roderick Ferguson terms it, and the sudden rise of decolonizing rhetoric without action particularly around land acknowledgments mark just a few sites of much contested ground within higher education.