The first thing I remember about “Chinese school” is the low fluorescent lighting in the community room we had rented from a local Baptist church. That low lighting has remained with me because it defined the space and our use of it as awkward. It was the seventies, the post-Watergate, pre-Reagan era, and by then, immigration patterns from Hong Kong, the People’s Republic of China, and Taiwan had become more diffuse, and in mid-sized cities like Louisville, Kentucky where I grew up pocketed populations had cropped up. These were not the immersive east and west coast Chinatowns and their sensibilities indexed that bicultural fact. The teachers didn’t like it, but it was in the mingling of Chinese and English — we students called it “Chinglish” — that we practiced our heritage.

Historians of heritage schools trace their arc alongside U.S. immigration legislation. The mid-19th century wave of immigrant labor informed the earliest heritage school mix of socializing and cultural preservation on the west coast, both responses to anti-Asian sentiment. When the Chinese Exclusion Acts (passed serially in 1882, 1904, 1911-1913) produced further immigrant isolation the heritage schools’ pragmatic — and ideological — centering of cultural preservation found firmer footing. That impulse towards cultural preservation actually continued post 1965, gaining steam as the U.S. relaxed its immigration stance, and Chinese American families began their move to white-dominated suburbs, taking heritage schools with them. By the 1980s, even the U.S. government had taken notice, observing that the “parallel” educational system demonstrated abilities in foreign language competency.1A View from Within: A Case Study of Chinese Heritage Community Language Schools in the United States, Xueying Wang, ed. Washington, D.C.: The National Foreign Language Center, 1996. The study was the first of its kind to focus “exclusively” on “heritage language preservation and enhancement” in the U.S., and the inaugural work of a proposed series.

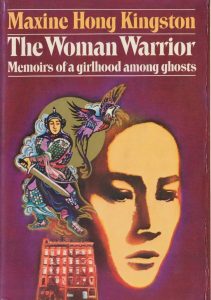

I am not an Asian Americanist by inclination or training. And my current book project — on the reading cultures of the women’s liberation movement — has little in common with heritage schools. Still, the call for this cluster made me think first not about the reading culture of consciousness-raising sessions, but rather about Maxine Hong Kingston. You may know that the contention over The Woman Warrior soon after its publication in 1976 was as much about how it ought to be read as its modes of representation. The quasi-memoir met with high praise (mostly from a white middle and highbrow readership) and ferocious critique (mostly from Chinese American male authors). Within the frame of literature and its extra-academic institutions, I found myself wondering what it means that my Chinese school moment (1978-1982) coincided with The Woman Warrior, but did not include it. This convergence is all the more striking given that the school curriculum — cultural nationalist in bent — bore a striking resemblance to the mythos in which Hong Kingston’s book is steeped.

I can be more specific. At Chinese school, my classmates and I wrestled with ink-tipped brushes on worksheet after worksheet, their dotted lines inscribing the proper brushstroke order. We practiced traditional folk dances, handkerchiefs draped over our wrists, to the strains of the Beijing Opera. We rolled out dough into circles thin enough to satisfy visiting grandmothers who then taught us the trick of folding them for pot stickers. We memorized short poems, usually from dynastic eras, for recitation, and listened to folktales about beautiful demons that preyed on peasants. A mix of literacy, arts, foodways, folklore and literature constituted the model of heritage we received.

The Woman Warrior offers much the same mix. To think in timeline terms, Hong Kingston and I both attended Chinese schools, she in 1950s California, me in 1970s Kentucky. By the time I started attending in that Baptist church, she had seen The Woman Warrior sell over 100,000 copies. I think it’s fair, then, to suggest that our Chinese schooling demonstrates a constancy of heritage thinking. This constancy was at work in the cultural activism driving Asian American fiction and theater of the late 1960s, for some a Third World Liberation front expression of political energies. And the energy of that moment fueled the intellectual literary energy of Asian American Studies.

At the same time, The Woman Warrior made a very American splash, published by Knopf, reviewing strongly in major outlets, winning the National Book Critics Circle Award, and appearing on college syllabi within the decade following. Its capture of a more public, mainstream fancy meant that The Woman Warrior became a text to be read for cultivation. Whose cultivation, though? Here the aspirational impulses of middlebrow reading are worth noting. Thus even if the Book of the Month Club did not feature The Woman Warrior in 1976, the BOMC vision of a “general reader” who is also a “book lover” dovetailed — oddly — with a heritage discourse encouraging U.S. readers to learn from, to expand their horizons with, The Woman Warrior.

That coincidence is nowhere more apparent than in the 1970s, when the publication of The Woman Warrior coincided with the moment when Chinese American families, driven by their own middle-class aspirations, began moving to the suburbs. How might the school have asked my classmates and I to read Hong Kingston’s book? To what extent might The Woman Warrior have imagined us, the bi-cultural children of immigrant parents who spoke more English than Chinese and who hardly read Chinese, as one of its readerships? We would have read The Woman Warrior in English, because English is its native language. However much heritage schools have regarded fostering literacy as an act of away-from-homeland identity formation, and literature and literary folktales as vehicles of similar national and ethnic investments, and however much we practiced Chinese at Chinese school, the fact remains that none of us could read Chinese.

Our base knowledge of character and vocabulary was that limited. That’s a form of linguistic alienation Hong Kingston describes, and it’s enacted in The Woman Warrior’s practice of both Chinese and English. It’s a form of cultural melancholia our teachers would have confirmed in their accounts of home and nation. The heritage school would have trained us to read a melancholic cultural nationalism present in Hong Kingston’s book, which itself mirrored the school’s view that literature could (and should) form and reflect ethnic character.

This essay is part of our cluster on alternative institutions. Visit this page to read the other essays.

Notes

- 1A View from Within: A Case Study of Chinese Heritage Community Language Schools in the United States, Xueying Wang, ed. Washington, D.C.: The National Foreign Language Center, 1996. The study was the first of its kind to focus “exclusively” on “heritage language preservation and enhancement” in the U.S., and the inaugural work of a proposed series.