The New Criticism and the expanding mid-century university system that made it possible shaped the establishment of racial liberalism in the U.S. via an untenable alliance between Southern reactionaries and industrial capitalists against labor and a racialized underclass. This alliance made it difficult for certain types of literatures to be studied within the academy with respect to their social and political valences and actively excluded teachers and writers for whom those dynamics were their primary interests. This consensus has long made it appear as if there was a vacuum of any other type of critical activity, particularly by those excluded from the university: those on the political left, Black people, and women. The intense focus on the university for the development of literary study means that the present understanding of critical practice is severely limited.

In the mid 1940s, just before the Zook Commission advised the formalization of a community college system, the Communist Party U.S.A. helped to establish a robust network of adult education in New York and about a dozen other U.S cities. Distinct from mainline forms of higher education, these institutions were devoted to economic, social, and political democracy for the people, a popular front euphemism for the ideals of midcentury Communists, many of whom were on academic blacklists. In turn, these schools provided politically-directed courses on Marxism, cultural subjects of various kinds, social science, the history of capitalism and imperialism, the principles of community organizing, as well as on scientific matters.

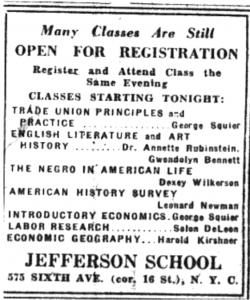

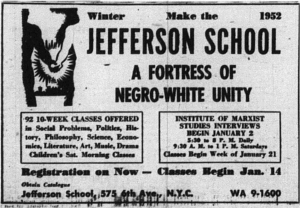

The Jefferson School of Social Science in New York—the largest in the system with 120,000 enrollments from 1944-1957—arose from a merger of two similar institutions: the Workers School and the School for Democracy. Using capital from Frederick Vanderbilt Field, a shell-organization, which was headed by Alexander Trachtenberg (the founder of International Publishers), purchased a multi-story furniture warehouse at 575 6th Ave in Manhattan for the Jefferson’s School’s use. This main building in Manhattan was outfitted with classrooms, a library, a bookstore, and a café and was soon filled with faculty purged from New York universities and students that were predominantly women, working people, and people of color.

Claudia Jones, Paul Robeson, and Lorraine Hansberry would appear at the Jefferson School and its affiliated institutions to teach, give lectures, and sometimes to fundraise. Other prominent figures on the Black left found a home teaching and learning there including Gwendolyn Bennett, Lloyd Brown, Elizabeth Catlett, Oliver Cox, and John Killens among others. W.E.B. Du Bois also taught several courses at the Jefferson School, one that included Hansberry and Childress as students. Du Bois saw great potential in the labor school idea. In a 1956 lecture it was reported by an FBI observer that he suggested that the Jeff School and the California Labor School in San Francisco “were the only two schools who tried to teach the people about the Negro position in their relation to the nation and the world.”

Du Bois’s argument encapsulates my interest in the Jefferson School and two closely affiliated institutions in Harlem, the George Washington Carver School, which operated from 1943 to 1947, and the Frederick Douglass Education Center, which opened in 1952. What interests me about these institutions is their teaching of Black literature and culture and of racial capitalism and imperialism. The cultural faculty—including Doxey A. Wilkerson, the director of curriculum who had left Howard University to join the Communist Party in 1943—identified the mid-century establishment of New Criticism within the mainstream academy as an inevitably revanchist movement. A collective statement from the school’s cultural faculty states that Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Robert Penn Warren are among the “reactionary forces” that have taken “control” of the arts. Despite widely being viewed in light of a populist reform, the work of these reactionaries is “saturated with racialisms, apologetics for slavery, deliberate distortions of American history, explanations of the most bestial violence as being ‘human nature.’”1“Draft Statement on the Position of the Jefferson School on Instruction in the Arts: Prepared as a Basis for Faculty Discussion.” Doxey A. Wilkerson Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, 1.

There is much more to learn about these institutions—and I offer more in my forthcoming book, Outside Literary Studies—but I want to focus quickly on three areas where an understanding of the Jefferson School and institutions like it can have significant repercussions on the history and practice of literary study, as well as our understanding of the development of American higher education.

First, these institutions prioritized cultural production in classrooms and in the political and aesthetic praxis these institutions supported. John Killens’ novel, Youngblood, which he wrote while attending Jefferson School lectures, carries the traces of labor school pedagogy in depicting the transmission of Black culture as a key part of political organizing and the book absorbs in its plot aspects of the complexities of the school’s commitment to Black-white solidarity in labor organizing. Works like Youngblood highlight that these institutions directly imprint the production of and understanding of Black left literature of the period. Understanding how these institutions supported otherwise banished modes of left and Black inquiry yields an impression of the mid-century forces shaping the development of Black literature, expanding our understanding of how Communism made space for the work of Black writers.

Second, the direct challenge to the New Critical hegemon by the Jefferson School opened interpretive modes tuned to working people, people of color, and women that were distinct from New Critical close reading. Labor schools spotlight a robust sphere of critical discourse, teaching practice, and cultural production operating largely independently of the university system. Its exclusion from the history of literary criticism reveals how at midcentury the bounds of literary critical thought ended at the walls of universities, certain publishing houses, and a few periodicals. This sets forward a historical trajectory that would increasingly insulate literature and its study from more direct arguments about the social and political relevance and legitimacy of these activities as they are described in academia. To work beyond that structure necessarily means investigating previously delegitimized critical activity among a number of minoritized writers.

Finally, understanding labor schools and their genealogy makes apparent an otherwise unseen force shaping the development of the postsecondary education system throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Cristina Groeger has suggested that at the turn of the twentieth, public education took shape as a reaction to an explosion of proprietary schools offering training in white- and pink-collar professions. Elite private universities in Boston, like Harvard and M.I.T., used their influence on public policy to discredit proprietary training and to shift other types of job training to secondary public schools while maintaining hold of executive credentialing capacity for themselves. In the same period, socialist institutions like the Rand School of Social Science, which was founded in 1906, developed in concert with industrial and craft unions to exert more control over worker-oriented education programs. Higher education institutions professionalized and expanded while making certain credentials more exclusive as a means to block emergent sites that challenged the reproduction of class and race.

This argument can be expanded to the mid-twentieth century, especially when one considers the need for capital to check labor’s accumulating power during and at the conclusion of World War II. The midcentury university expansion, as has been well noted, is directly tied to the continued growth of U.S. war materiel production and nominally directed towards reproducing citizens, rather than workers. Within this frame, U.S. higher education policy responds to the developments of these Communist affiliated institutions by the massification of a liberal consensus around a racially constrained form of capitalist democracy led in part by the seemingly reconstructed New Critics. Schools like the Jefferson School referred to themselves as “people’s schools” and the intense scrutiny they faced from the federal government suggest the position of mainline higher education institutions with respect to capital in the effort to define the material and rhetorical limits of democracy at the onset of the Cold War.

This essay is part of our cluster on alternative institutions. Visit this page to read the other essays.

Notes

- 1“Draft Statement on the Position of the Jefferson School on Instruction in the Arts: Prepared as a Basis for Faculty Discussion.” Doxey A. Wilkerson Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, 1.