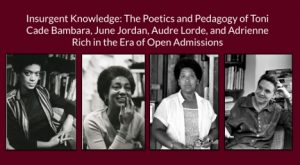

In the late 1960s, at the height of the era’s social movements, four of the twentieth century’s most important authors were teaching down the hall from one another at Harlem’s City College. Like the majority of educators today, Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, and Adrienne Rich were not teaching wealthy or even middle-class students at elite universities with ample resources. Rather, they were teaching working-class students and students of color at a massive, urban, public university. What brought these writers together was not merely fate, but the college’s new policies that expanded access to higher education. What began in the 1960s as a groundbreaking educational opportunity program would expand by 1970 into an open admissions policy that granted every graduate of New York City’s high schools a seat at one of its public colleges, free of tuition. At a time when mainstream media and traditional faculty were accusing these initiatives of killing higher education, these authors understood free college as crucial to the flourishing of marginalized communities. They treated teaching not as an ancillary obligation, but as a creative artform deeply related to their writing. And it was in these public college classrooms—not the ivy-clad towers of Harvard or Yale—that these authors became part of a teaching community that forever altered their lives and the course of literary and educational history.

For this forum, I want to say a bit more about these writers’ experiences teaching in the nation’s first state-mandated educational opportunity program. The SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge) program was established in 1965 to address the fact that City College, a school with a historical commitment to educating the working class, remained a predominantly-white institution amidst Black and Puerto Rican Harlem. SEEK recruited “economically and educationally disadvantaged” students and prepared them to matriculate at City College through remedial coursework, tutoring, and counseling. While SEEK would eventually become a model for similar programs nationwide, in these early years, its success was much less certain.

Despite the historic grounds this new program broke, many professors wanted little to do with it. English faculty refused to teach remedial writing, which they saw as dull, utilitarian service work. They viewed these courses as merely skills training and preparation for “real” courses on literature, biases that are still familiar today. While the old guard was uninterested, a number of up-and-coming authors were lining up at the door to teach in this exciting new program. This included Bambara, Lorde, Jordan, and Rich, as well as major writers of the Black Arts Movement (Larry Neal, David Henderson, and Raymond Patterson), scholars of Black literature (Barbara Christian and Addison Gayle), and composition scholar Mina Shaughnessy. Amidst a society that systematically devalued the lives of Black and brown students, SEEK educators saw remedial education, in Rich’s words, as part of a broader “movement for social change,” the goal of which was to “break down false barriers of class & color” and make education “open to all people who want it.” Despite the program’s modest, even assimilationist, aims of preparing educationally-disenfranchised students for college, what happened in these classrooms far exceeded this objective.1See Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ analysis of Lorde and Jordan’s “counterpoetic” pedagogy: “using spaces designed in service of the colonial project to protest that same project, with varying levels of success.” “Nobody Mean More: Black Feminist Pedagogy and Solidarity” in The Imperial University, ed. Chatterjee and Maira, 242. Indeed, it was in these access-oriented classrooms that these writers developed creative methods of teaching students to advocate for social change.

In the book-length version of this project, I explore how such methods were shaped by the era’s social movements, as well as the ways their teaching shaped their literary works. For this forum, I’ll offer a few observations about the role of literature in their pedagogy.

1. In the SEEK program, these authors involved students in making collective decisions about their learning, including what they would read, how their work would be evaluated, and the terms by which they would participate in the course. Such student-centered approaches were a response to the years of educational racism SEEK students had been subjected to: substandard conditions, outdated teaching methods, and instructors more interested in disciplining students than nurturing their intellect. Bambara called this “the criminality of education.” In order to help students unlearn years of disciplinary schooling and cultivate a different relationship to learning, these authors centered students’ curiosities, desires, and intellectual interests.

Given the opportunity to study anything in the world, what these students wanted to learn more about were topics like race and colonialism that had been absent from their own formal educations. One semester, for instance, Bambara’s students designed a course on “Colonialism, Neocolonialism, and Liberation” in which they studied the recent liberations of African nations, the imperialist war in Vietnam, and the “internal colonialism” of U.S. racism. In addition to reading newspaper articles from a variety of sources, they read books like Eldridge Cleaver’s prison memoir Soul on Ice and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and discussed its influence on radical movements. While traditional courses gradually progress towards a final research project, Bambara’s students performed research from day one. Any time they encountered an unfamiliar topic, such as “Senghor and the Negritude Movement” or “Pan-Africanism,” Bambara sent students out to locate the knowledge that had been withheld from their own educations. They dug through the shelves at City College’s Cohen library, performed archival research at the Schomburg Center, scoured their neighborhoods for newspapers, and conducted oral histories with their friends, families, and community leaders to find those perspectives deliberately obscured by power.

2. In their SEEK courses, these authors assigned works of literature not solely as texts to be analyzed, but as sources of inspiration for student writing. In what I’ve been thinking of as creative mimicry assignments, they coupled readings by Richard Wright and Amiri Baraka with assignments that challenged students to experiment with each author’s literary techniques in their own writing. For example, when they read Baraka’s essay “Cuba Libre,” analyzing the lies and distortions in mainstream journalism, Bambara gave students an assignment to write about “the lies they encountered growing up…brotherhood, melting pot, land of the free and the home of the brave.” Often, especially in Jordan’s and Rich’s courses, the texts they selected for creative mimicry– like Alfred North Whitehead’s The Aims of Education or George Orwell’s scathing critique of his boyhood boarding school, “Such, Such Were the Joys”– helped students analyze the schools in which their lives were unfolding. For students who had been told that they were wrong from the moment they first set foot inside white-dominated classrooms, these assignments taught them that their lived experiences were valid grounds from which to analyze the world, critique dominant institutions, and intervene in political debates.

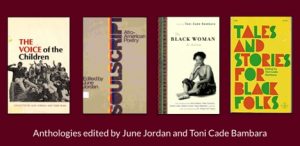

3. In contrast to the era’s dominant deficit paradigms, which emphasized the reading skills that SEEK students lacked, these authors saw their students as capable not merely of reading complex literature, but of writing it. During this period, both Jordan and Bambara edited anthologies that included student writing. Some of the collections contain student work alongside that of literary luminaries like Langston Hughes and Alice Walker; others are written entirely by students. Though these anthologies are more famous for other things–Soulscript (1970), as a groundbreaking collection of African-American poetry and The Black Woman (1970), as a landmark text of Black feminism–we can also think of them as final projects that emerged from Jordan’s and Bambara’s classes. In a pedagogical sense, these published collections helped students understand how their voices could impact readers beyond the classroom. Amidst curricula that reflected the values of a racist society, such anthologies offered correctives to the classroom’s “typical textbooks,” with their omissions and distorted visions of Black life.

If, as Rachel Sagner Buurma and Laura Heffernan have compellingly argued, histories of literary studies have overlooked the space of the classroom, this seems doubly true in the kinds of basic writing classrooms these authors taught in, which continue to be seen as sites of mere skills training and preparation for more advanced coursework. Yet it was in such classrooms that these authors developed creative methods of teaching literature—and writing—as part of a consciousness-raising education. There, the literature they read filled in the gaps of a capitalist, white supremacist curriculum, and modeled ways that students could also address such gaps in their own writing. Literature, in this paradigm, helped students generate insurgent knowledge: the ideas and perspectives missing from mainstream media, journalism, and curricula. Considered together, their work illustrates how basic writing classrooms have been sites not only for the reception and dissemination of literature, but also its production.

This essay is part of our cluster on alternative institutions. Visit this page to read the other essays.

Notes

- 1See Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ analysis of Lorde and Jordan’s “counterpoetic” pedagogy: “using spaces designed in service of the colonial project to protest that same project, with varying levels of success.” “Nobody Mean More: Black Feminist Pedagogy and Solidarity” in The Imperial University, ed. Chatterjee and Maira, 242.