2021 was a banner year for jaw-dropping endowment returns for U.S. colleges and universities. On average university endowments grew by 30.6%, though some school’s netted even more: eight institutions grew their endowment by more than 50%, according to Pensions & Investments. This growth appears only more stark when put in relief with the continued increase of student debt, a cumulative total that now exceeds $1.7 trillion. These figures have become a way to express the wealth accumulated within higher education seemingly at the expense of students. Together student debt and endowment returns indicate that finance stands as a key element in tethering together the heterogeneous set of institutions that make up the system of American higher education.

Charlie Eaton’s new book, Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in Higher Education (Chicago, 2022), suggests that these financial instruments can generatively be understood as the result of social ties. With this analytical frame, Eaton offers crucial data points for assessing the shape of the current situation (“Colleges and universities…paid an estimated sixty cents to hedge funds for every dollar in investment returns between 2009 and 2015”) and, importantly, an understanding of how finance connects institutions at the top, middle, and bottom tiers of American higher education. That is, by foregrounding finance, Eaton identifies the connections between elite university endowments and student debt, as well as between for-profit colleges and private nonprofit institutions. When seen through the lens of the social dimensions of finance, these connections reproduce, rather than redress extant forms of inequality and even produce novel means for social stratification.

Our Associate Director, Andy Hines, spoke to Charlie Eaton, Assistant Professor of Sociology at University of California, Merced, in late January 2022. The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

Andy Hines (AH): This is a book about finance and its role in shaping higher education policy and higher education institutions, but perhaps to the surprise of some readers the book is deeply interested in social connections, what you term the “social circuitry of finance.” Why is it important to think about social connections when thinking about finance and higher ed?

Charlie Eaton (CE): When people think of finance they think “cold, calculating, rational.” Maybe they think of Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street and his mantra that “greed is good.” But part of what I wanted to show is that there’s actually quite a bit of intimacy in the social relationships of financiers.

The social circuitry of finance and intimacy are terms that I first started thinking about from reading Fred Wherry’s work on social circuits of commerce, as well as Viviana Zelizer’s work. But even when you read stuff about financiers written by economists and journalists, you find that they talk a lot about private information.

A big part of what hedge funds and private equity funds do is they try to make money by making investments, based on private information, that people in public markets don’t have. If you’re a hedge fund trader and you decide you want to short a stock, for example, you think that a stock is overvalued on the stock market because, based on public information, most people who buy stocks don’t know that this stock is overvalued. For instance, there were a bunch of hedge funds that tried to short-sell for profit college stocks when they thought that consumer protection regulations were going to lead to a collapse in for profit college profits and they were mostly right.

For Zelizer and Wherry, intimacy is really about the sharing of private information. Intimacy is a useful concept for thinking about questions like, “who do you share private information with” and “how do you get private information that’s not shared publicly.” The social relationships that people form in college and that they maintain via what I call the parallel social circuitry of social organizations, or, more concretely, universities.

Social organizations are potentially valuable sources of private information for financiers. This information and this intimacy stems from the relationships financiers form in college, the shared identity of being an insider, a member of the elite who graduated from Harvard or Princeton or Yale. Being willing to share your private knowledge with other insiders is a way to maintain those identities and those networks that financiers form.

AH: You write about how finance stitches together a stratified system of colleges and universities and the students who attend them. Could you describe what links the “bottom, middle, and top” and why finance is a pivotal vector through which to understand the present formation of a U.S. higher education system? What made finance a force for shaping higher education institutions and policies in the first place?

CE: I started with the intimate relationships between financiers and and in the book I particularly look at those intimate relationships around university board members and around university endowments.

An example of an intimate relation I talk about in the book is Tom Steyer, the hedge fund billionaire who ran for president and has done a lot of philanthropy to support social movements that seek to address climate change. In the 1980s Steyer told people that he heard that a fellow Yale alumnus David Swensen had been appointed to manage the Yale endowment and that Swensen was starting to make hedge fund type investments using the endowment.

Steyer learns this private information at a Yale homecoming football game and then uses his intimate relationships to get a meeting with David Swensen. Steyer spends two years convincing Swensen to invest in his hedge fund. In a New York Times profile of Swensen titled “For Yale’s Money Man, a Higher Calling,” Steyer tells the interviewer—and I’m paraphrasing: “David initially turned me down and I had to promise him that we wouldn’t shut down, even if we made money at first. Swensen didn’t want Yale to take a loss, so I also had to swear that we wouldn’t take our 20% share of profits initially.”

There’s a real sense of honor and trust among fellow Yale alumni. As a result, David Swensen gave Tom Steyer $300 million from Yale’s endowment, which was a third of the initial capital that Steyer raised for his hedge fund.

I also talk about financiers as transistors in the social circuitry of finance. They do a lot of coordination that requires trust and private information, which is consistent with the old Granovetter problem of embeddedness. That is, how do people coordinate and how do they trust each other if they have to coordinate?

Another example of that coordination is Jonathan Nelson, who is a board member at Brown University. He founded the Providence Equity Capital private equity firm that made him Rhode Island’s only billionaire. In 2006 his firm carried out the largest ever buyout of a for-profit college chain when they acquired the EDMC education management corporation and its Art Institutes chain and other schools. His firm couldn’t do that by itself. They needed some knowledge of the sector and so they partnered with another firm called Leeds Equity Capital, led by Jeffrey Leeds, a Yale alumnus, and with Goldman Sachs, where the Managing Director for the acquisition was a Harvard Business school alumnus. Jonathan Nelson received his undergrad degree from Brown and many of the top managing directors in his firm are Brown alumni. Different people brought capital to the table, others brought leads. There was a lot of intimacy, coordination, and trust involved in this deal.

As transistors, this private equity firm carries out what I call unidirectional intimate relationships to essentially exploit for-profit college students. I use a lot of data, but I also tell the story of Kim Tran, Don Quijada, and Alyssa Brock, three students who went to New England Institute of Art, one of the colleges that was acquired and essentially ransacked by this private equity firm. A number of these students recently had their loans canceled because of a lawsuit brought against EDMC for fraud alleged by the Attorney General of Massachusetts.

Kim Tran grew up 15 minutes away from where Jonathan Nelson has lived for the last few decades in Rhode Island. She definitely didn’t benefit from the $50 million donation he gave to Brown for which he had the recreation center there named after him. The recruiters who worked for EDMC on Jonathan Nelson’s behalf gathered lots of intimate information about Kim, Alyssa, and Don when they were recruiting them. The recruiter who recruited Alyssa had gone to the same college in Maine that Alyssa’s mom had attended. That and other information was private information that the recruiter obtained and then used as part of the recruitment process. Finance gathered and used that kind of private information to enroll students, to load them up with student debt, and to take in a bunch of tuition revenue from that student debt, all while providing essentially no educational benefit to students.

In the other direction, students did not have access to private information about the New England Institute of Art. They certainly didn’t know that it was owned by a private equity Wall Street investor. They didn’t know that it had terrible graduation rates. They didn’t know that the student loan repayment rates were terrible and that they will be taking on substantial risk by taking on debt to go to that school. That’s another way these social relationships get connected by finance.

There is one more layer to this. There’s certainly intimacy between people like Jonathan Nelson, Tom Steyer, and university leaders and endowment managers. Providence Equity Capital had capital from seventeen endowments when it acquired EDMC, capital that they raised through intimate relationships. At the same time, there is a passive and almost unknowing connection of students and faculty at elite colleges to this exploitation at the bottom that occurs through these ties. College endowments did not cause the wholesale exploitation of overwhelmingly working class, disproportionately Black, for-profit college students. But they did via a mechanical resource transfer benefit in that the profits earned by for profit college investors were passed along to their endowment investors.

AH: This has me thinking about something that Louise Seamster has talked about, mainly that debt has come to be a means by which people access citizenship and the world of shared social production. This is distinct from previous modes of citizenship more directly tied to the state. This story about debt maps on to the ways that the function of higher education is often narrativized, moving from an institution devoted to the reproduction of a citizenry in the mid twentieth century towards the more contemporary sense of an institution with a direct connection to the labor market.

How do you narrate that transition from institutions that are nominally serving a state-related and public purpose versus those that are more devoted to creating social forms through instruments like finance?

CE: Yes. This is interesting because it makes me think of Seamster’s work and the notion of black debt and white debt, good debt and bad debt. While debt can be a social relationship of inclusion and status attainment, it can also very much be a relationship of exclusion and status subordination.

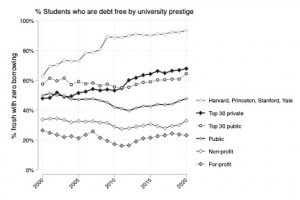

An example: the first figure in the book shows the percent of students who go to colleges debt free by these different strata. Students who go to the top 30 private schools overwhelmingly go debt free. I’ve since updated that figure to add five more years of data and to break out Harvard, Princeton, Yale and Stanford. When I do that, it shows that today, and for the most part for the last ten years at those four top schools, only 7 to 8% of students borrow at all while they’re in school. These are the same schools that Raj Chetty has shown enroll more students from the top 1% of the income distribution than from the bottom 60% combined. So to attend those schools, students don’t have to take on debt because they come from means; and Caitlin Zaloom has done good work on why these parents feel that they are bad parents if their child takes on debt.

At another level, students of means have the privilege to not take on a student loan because with their parents students can locate an interest rate better than the standard 6% rate on student loans. For much of the last two decades, families could get a home equity loan and a home loan and borrow at 2%, effectively arbitraging home wealth to pay a much lower debt. At the same time, for the few folks that borrowed when going to these colleges, if they are making lots of money after graduating and they have a 6% student loan on their books, they can refinance to a lower rate by going to a private lender. A private lender will not give someone a lower rate to refinance a federal loan if they are making $20,000 a year for example.

While loans might be a vehicle for social inclusion, they’re also, to use Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy’s term, “classifications systems.” They classify who is worthy of low interest rates and who is not worthy of low interest rates.

AH: How then does that classification system map onto the stratified system of higher education?

CE: There are multiple overlapping stratification and classification systems at work here. One is the classification system of how much debt someone holds and with what interest rates and what terms. There’s also the classification system of how prestigious and elite the school is that a person attended. This is also overlaid with the classification system of race that has defined America since its inception.

An expression of that overlap is that at their peak for-profit colleges enrolled more black students than all private non-profit colleges in the US combined. This was not true for other racial groups.

Another manifestation of this overlap is that Black borrowers tend to owe the same amount that they originally borrowed in student loans 20 years after they started school. People might ask how that is even possible? It is not because they weren’t making payments. It is because they couldn’t afford to pay principal down and their interest compounded. They may have paid off $80,000 on a debt of $40,000 and still owed $40,000 20 years later, for example.

We know from work by Fenaba Addo, Jason Houle, Mark Huelsman, Louise Seamster, Tom Shapiro, and others that much of this disparity is rooted in the racial wealth gap. Black students do not have the same household wealth to draw on from their parents in order to borrow less and to get assistance to repay loans later. Racial discrimination in the job market and lower earnings because of racial discrimination after college, despite having earned a degree, is another mechanism by which the racial classification system in the US maintains these racial inequalities in student debt.

Student debt, in turn, maintains the racial wealth gap, because you can’t buy a home, get a car loan to buy a car, or, as Don Quijada told me, he couldn’t get a $200 revolving line of credit at a music equipment store to buy equipment for the sound studio he was building for his own business. Similarly, people facing this crunch likely do not have disposable income to invest in financial assets like stocks or index funds for a retirement fund.

Those are ways that classification systems of student debt and race work together to maintain wealth and class, another racialized classification system.

AH: You write that “student debt disadvantage is a new economic inequality that was virtually nonexistent before the 1990s.” You’ve already elaborated on what might lead to this a little bit, but could you say more?

CE: The counterargument from the economists about the problem of student debt being a new inequality is that people will make more money if they go to college by taking out a student loan than what it costs to ultimately repay the loan. And therefore it is actually better for people to take on that loan. The problem is the counterfactual is wrong.

The counterfactual centers the individual choice that somebody makes: am I going to go to college with a student loan or am I not going to go to college? And yes, you’ll be better off if you go to college with a student loan than if you don’t. But as a society we’ve essentially decided instead of paying for everybody to go to college debt free that we’re only going to let wealthy people go to college debt free. So the situation boils down to whether you leave college without a debt or with a debt. This is a new inequality that we ask a set of people to undertake: to start their adult lives and their careers with a debt that they would not have had in the past and that they would not have if they were from a wealthy background.

This inequality did not exist in the 1970s when only 1 in 8 undergraduates borrowed at all. Relatedly, millennials, who are more racially diverse and more commonly not white than the baby boomers, have as an entire generation only one seventh of the household wealth compared to what the baby boomer generation had at the same age in 1989. It is clear that while it is individually a good choice in our current social structure for people to go to college with loans, as a society we’ve made it a choice that imposes a new inequality on classes of people.

AH: We started this conversation by talking about the social. One of the things I think is particularly important about your book is that it is clear about how institutions that are often compared—UC Berkeley and elite private institutions for instance—reproduce different social formations, even if both are selective and carry a high sticker price. At the end of the book, you write about multiple forms of social and political organizing and the differences in their strategies: how do the social formations made through social movements diverge from that made by universities? What do you make of this divergence and what ought the relationship between the two be? Should the university strive to build the kind of social formations wrought in social movements, for instance, or should social movements gain more authority of various kinds for serving this crucial function?

CE: Since the rise of mass higher education in the US in the 1950s, universities have played major connective roles in multiple social movements, including the Civil Rights movement, the Farmworkers movement, and, more recently, Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter to name just a few.

In describing his work on the Farmworkers, Marshall Ganz describes how universities were one source of borderlands actors that helped create strategic innovation in the Farmworker movement. Farmworker organizers, including Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and Fred Ross, made an explicit point of mobilizing students, including Marshall Ganz who was from Bakersfield and was an undergraduate at Harvard. Organizers mobilized and deployed students to help lead the grape boycott when farmworkers were trying to end dire inequalities and poverty among grape pickers in California.

In the book, I talk about the California iteration of Occupy Wall Street and how public universities played a key connective role there and in the subsequent mobilization and passage of a tax on millionaire income earners, known as Proposition 30. Ten thousand students walked out at Berkeley in November of 2011 to demand tuition freezes and taxes on millionaires. This set off a wave of protests at UC Davis and at other public universities in the state. Ultimately, that tax increase and a tuition freeze were negotiated in the state in large part by more economically diverse alumni of the University of California and California State University system, including UC student association President Claudia Magaña; UC alumnus John Pérez, who was the speaker of the California Assembly at the time; Max Espionza, Pérez’s top higher education staffer who had been the UC student regent and a student leader at UCLA; Josh Pechthalt, who was the president of the California Teachers Association; and Jerry Brown, the governor of California, who was himself a UC Berkeley alumnus. You can just hear the different social positions that these folks are coming from and their organizational affiliations were much more diverse than the alumni network of Harvard in 2011. This played an important connective role for these social movements and for translating social movement demands into policy change. There are similar ways that this happened around Occupy Wall Street on the east coast, particularly around the project of student debt cancellation.

AH: Thank you!

CE: I wanted to note that I pulled the book down from the shelf at one point when we were talking because I wanted to be sure that, in fact, Swarthmore was one of the 17 college endowments invested in the private equity firms involved in the EDMC buyout. This is not a judgment thing; it is really to understand our connection to these activities. All of us working at universities need to ask who among us doesn’t have a billionaire private equity investor on our board. We certainly have one in the University of California system. His name is Dick Bloom and his wife is California’s US Senator, Dianne Feinstein.

In other words, despite the paradoxical position that we’re in, what can we do for the project of financial and social equity in higher education and beyond?